Developing innovative efforts to reduce crime and social disorder is an integral part of modern police work. Police agencies that undertake such interventions should consider advertising their work and ideas. Departments can help remove crime opportunities by teaching and encouraging the public to adopt better self-protection measures, or they can warn offenders of increased police vigilance or improved police practices. When designed properly, publicity campaigns can offer police departments another problem-solving tool in the fight against crime.

There are many different ways that the public can learn about a police crime-prevention initiative. There could be a news story detailing the initiative, people may hear about it through word of mouth, or newspaper editorials may mention it. All of these “sources” do in fact publicize the initiative, but there is little control over the content or its portrayal. To separate this kind of general information from a crime prevention publicity campaign, the term crime prevention publicity should refer to:

This definition focuses on clearly defined efforts that incorporate information with practical crime prevention measures.

Publicity serves to pass relevant information to potential offenders and victims. Informing a community about a crime problem, introducing target-hardening measures, or warning of increased police patrols can lead to an increase in self-protection and/or a decrease in offenses.

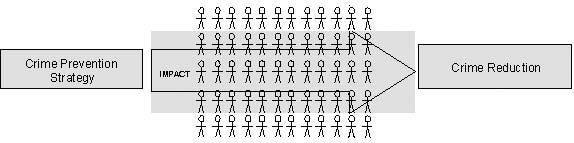

The figure below shows the impact of a stand-alone (no publicity component) crime prevention strategy aimed at offenders. While the initiative does manage to deter or help police apprehend a segment of the offending population, many offenders remain unaffected. This is partly because in this kind of scenario, the crime prevention benefits are limited to those who have heard about the operation or who have been directly affected by it.

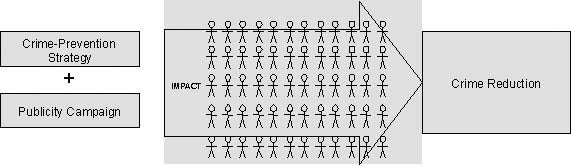

In the following figure, a complementary publicity campaign advertises the same crime prevention strategy. Through the advertisement, however, a bigger segment of the population hears about the strategy, and more crime reduction results.

Publicity campaigns in crime prevention operate much like advertising campaigns in the private sector. Commercial advertisements are intended to persuade a target audience to buy a particular product by publicizing information meant to appeal to that audience. Effective commercial advertisements therefore sway customers to change their behavior, usually by buying something. When it comes to crime prevention, the same dynamics are at work. Those targeted by the intervention (offenders and victims alike) need to be exposed to information that will influence their future decision-making processes. The key is to devise proper campaigns and to match the message to the audience. There are numerous ways to use publicity, and agencies can benefit from succinct and properly designed campaigns to support crime prevention efforts. This guide’s purpose is to help local police plan and implement effective publicity campaigns by exploring their benefits and pitfalls.

Police agencies should not blindly resort to publicity campaigns or rely on them to replace proper police interventions. While it may be tempting to adopt publicity campaigns to support police efforts, such attempts should incorporate proper planning and adequate implementation. A poorly designed publicity campaign may inadvertently increase fear of crime, with undesired consequences such as vigilantism. Police agencies should also refrain from relying on publicity campaigns as a generic response to crime problems. Randomly posting signs advising residents to lock their cars is unlikely to reduce a city’s car theft problem. Publicity campaigns should always complement police initiatives, and police departments should be wary of relying on publicity alone to combat crime.

Police should also remember that repeatedly relying on campaigns meant to scare offenders without implementing concrete programs or enforcement is essentially “crying wolf,” which harms police-community relations and causes no crime reduction.

Before mounting a crime prevention publicity campaign, police should carefully analyze the crime problem. For instance, if a burglary analysis indicates that victims would benefit the most from prevention information, then a campaign is more likely to succeed by focusing on educating victims. Agencies should therefore undertake a publicity campaign only in the context of a broader response to a problem.

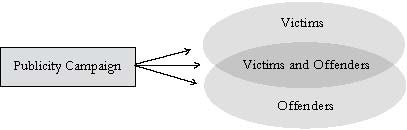

Police publicity campaigns target two main audiences: potential victims and offenders. Law enforcement agencies should decide which audience to target based on the nature of the problem. For example, if a police department notices that there are numerous preventable property crimes in an area, perhaps a short campaign to remind residents about the importance of securing their belongings could be beneficial. On the other hand, if local youths routinely vandalize cars in a parking lot, a campaign threatening police apprehension would be more effective. However, nothing prevents a dual approach whereby two campaigns run simultaneously, one to reduce the number of potential victims, and the other to deter offenders.1The figure below illustrates this concept.

When trying to determine the target audience, one should also consider how accessible each audience is. For example, a victim-oriented campaign designed to reduce car break-ins by mailing fliers to local residences is not appropriate if most of the victims are commuters from out of town. Likewise, putting up posters aimed at car thieves in retirement facilities is unlikely to reach the intended audience. Therefore, “audience accessibility” should guide the campaign’s direction.

Efforts to reach victims can take one of two forms. Police can try to provide general information to residents concerning crime and its prevention, or they can advertise a specific community program they are undertaking. The goals of general campaigns are to raise awareness in hopes that some members of the public will avoid victimization. The second type of victim campaign focuses on a particular crime and offers victims concrete steps to avoid victimization or reduce their fear of crime.2These campaigns often involve cooperation between the police department and the community in conducting home-security surveys, obtaining steering-wheel locks, or providing classes on various security-enhancing measures. Fliers and newsletters demonstrating techniques to make cars and houses “burglar-proof ” are common in these “target-hardening” campaigns.

General publicity campaigns aimed at victims have had limited effectiveness.3A four-month national press and poster campaign tried to educate people about the importance of locking their parked cars, but it failed to change people’s behavior.4Another campaign used posters and television spots to remind people to lock their car doors, but it also proved ineffective.5These studies demonstrate that people often pay little attention to crime prevention messages. A common reason given is that potential victims do not feel that it concerns them.6For instance, domestic violence awareness campaigns have to compete with the possibility that women do not want to see themselves as victims.7

Some other explanations include community members’ feeling bored by the message, not seeing the message, ignoring the message, or adopting the “it won’t happen to me” mentality. Even with extensive campaign coverage, general publicity attempts show meager results. A five-week police campaign showed that “despite an unusually high level of coverage, [the campaign] failed to influence the number of car thefts known to the police or the proportion of drivers locking their cars.”8In Canada, a mass media campaign to promote crime prevention relied on radio, television, newspapers, and billboard advertisements. This general campaign attempted to target three different property crimes: vandalism, residential burglary, and theft from automobiles. Although the campaign reached a large segment of the population, only a small number perceived the crime prevention themes as relevant or worthwhile.9

However, victim campaigns that focus on specific crimes and are carried out in small geographic regions seem to be more effective.10They seem to have more success because people feel the messages are more relevant to their immediate situation than are generic warnings about crime. A good example of this type of campaign was carried out by the North Brunswick Police Department in New Jersey. In 1998, the department decided to address auto thefts through a multimedia publicity campaign. The campaign included television public service announcements (PSAs), newsletters from the mayor’s office, crime prevention brochures, community bulletin boards, and local billboards, among other measures. The effort also included the donation of free Clubs® from local businesses. By attending local community functions, the police could reach many residents, effectively disseminating specific crime prevention information. One out of three residents reported some contact with the campaign, and of those, nearly all adopted the proposed crime prevention measures, significantly reducing auto crimes.11

Sometimes, victim publicity campaigns reduce crime because they alert offenders that the police are doing something new or are paying more attention to the problem.12While warning offenders is not an intended part of the campaign, the message still reaches them. A property-marking project in the United Kingdom was successful because the publicity surrounding the police intervention inadvertently informed potential burglars that measures were under way to address the problem.13Similarly, a police campaign to reduce car theft by inviting residents to etch a vehicle identification number (VIN) on their cars was an unexpected success because it deterred potential offenders by alerting them to the prevention measure.14

Crime prevention strategies rely on the notion that offenders are rational individuals who seek to maximize their rewards while minimizing their potential costs.15With that premise, giving offenders information about the risks of crime becomes an important component of crime reduction efforts. Police agencies can use publicity to advertise the risks offenders are taking, either by showing the increased level of victim protection (thereby reducing the potential benefits), or by highlighting the legal consequences of crime (increasing the costs). Costs to the offenders can range from bodily harm, to legal sanctions, to societal impacts. Boston’s efforts to reduce gun crimes included a publicity component that proved to be quite effective because the campaign’s message “delivered a direct and explicit message to violent gangs and groups that violent behavior will no longer be tolerated, and that the group will use any legal means possible to stop the violence.”16

Some examples of campaigns focused on legal consequences or making moral appeals include “DON’T DRINK AND DRIVE,” “SHOPLIFTING IS A CRIME,” and “SPEEDING KILLS.” However, evaluations have found that this type of publicity campaign rarely has an impact.17Perhaps, as with victim campaigns, offenders do not take the message seriously, or they do not feel it applies to them and dismiss it as irrelevant. Many offender campaigns are also ineffective because they deliver information at times when people are not committing crimes.18In short, the campaign organizers should ask themselves: “How do we make it relevant to the offenders’ immediate situation?”

Publicity campaigns that threaten an increased risk of arrest can be more effective in reducing offending.19Campaigns that threaten only eventual punishment lack the element that plays an important role in the offender’s mental equation: the probability of getting caught.20When a police department engages in crime interdiction efforts, the risk of arrest should be the primary advertised message—not the effect of an arrest, but the probability of an arrest. In reality, this is hard to quantify, but the purpose of the publicity is simply to alter offenders’ perceptions, leaving them to wonder when and where they will be caught.

Offender campaigns are successful not when they threaten later punishment, but when they threaten detection and arrest. The Operation Identification and VIN initiatives discussed earlier were successful because the publicity warned offenders about increased police attention. In England, signs on buses that warned youths that they were being watched via CCTV, and that infractions would be reported to the police, significantly reduced bus vandalism.21

Campaigns designed to reduce speeding also support the use of threatening apprehension. Speed limit signs and posters demanding a slower pace have had little success in deterring speeders. However, speed cameras and publicity about the high likelihood of getting caught have proved to reduce the speeds of even the most dedicated of offenders.22Placing posters warning that officers are around the corner to surprise speeders is a good example of effective offender publicity.23

Finally, offender campaigns are more efficient when they target specific crime types and focus on a clearly defined geographic area.24For offenders to take the message seriously, they need to feel as though the campaign targets them directly. This need to be specific requires police agencies to know whom they are targeting, at what times, and in what areas. For example, a police initiative to reduce car vandalism after school hours can include posting signs around town stating that “VANDALISM IS A MISDEMEANOR,” but a more focused approach might include posters in the problem area with messages such as “SMILE, UNDERCOVER OFFICERS ARE WATCHING YOU,” or “OUR OFFICERS HAVE ALREADY ARRESTED 12 STUDENTS FOR VANDALISM—WILL YOU BE NEXT?”. By focusing on distinct areas instead of trying to cover an entire city, police officers can concentrate their publicity resources on one setting, avoiding the risk of spreading themselves too thin. This targeted approach also allows personalization of the message, making it more believable and pertinent to the local audience.

Crime prevention efforts that include publicity components need to address the campaign’s cost-effectiveness. Police agencies have numerous media options to promote their message, each with differing costs and convenience. As mentioned above, the different formats range from television campaigns to common fliers. With proper planning and organization, most police departments can undertake a publicity campaign with minimal costs.

A key consideration in the cost of publicity campaigns, especially ones that involve signs and/or posters, is that their visibility be constant, allowing agencies cost-effective message dissemination. While other components of the intervention may be in effect only when people are actively promoting crime prevention measures, a posted sign is always “at work.”

Police agencies can also reap indirect benefits by initiating publicity campaigns, including the following:

Research has shown that when a publicity campaign advertises an upcoming police intervention, crime reduction benefits may occur before implementation. This phenomenon is called “anticipatory benefits.”27This occurs when the pre-intervention publicized warning alters offenders’ perceptions of risk. Thus, police agencies can maximize their crime reduction potential through the early advertising of future prevention efforts.

Sharing information, be it offering crime prevention tips to potential victims or trying to warn offenders about increased risks of arrest, inevitably draws attention to a community’s crime problem. Police may therefore encounter some opposition to mounting a crime prevention publicity campaign from influential community members.

For example, a car theft campaign in a local shopping-mall parking lot may meet resistance from business owners who fear the campaign may scare away potential shoppers. Real-estate agents opposed anti-car theft publicity posters in one New Jersey town when clients became apprehensive about living in an area with a high car-theft rate.28Other businesses that may express concern include tourism bureaus, entertainment venues, and educational facilities. Finally, local politicians may not approve of advertising crime problems in their jurisdictions, regardless of the potential prevention benefits.29These examples highlight the importance of working closely with community stakeholders when developing and implementing publicity campaigns, as there may be competing interests at play.30

Publicity campaigns can sometimes result in residents’ becoming unduly alarmed about relatively rare crimes.31Sometimes, this might lead them to take crime prevention matters into their own hands (such as by carrying weapons).32Therefore, campaign messages should avoid sounding too alarming or providing unnecessarily frightening information. Campaigns should address their targets directly, avoiding words that may alarm a community by highlighting a crime problem. For example, an anti-car theft campaign should avoid the following message: “This neighborhood is working to drive car thieves out”. This sort of message may raise unnecessary community concerns about car thefts. A more appropriate campaign may state: “Car thieves are in for a ride – straight to jail”. A further undesirable result of some campaigns might be citizens’ belief that police intrude too much in their daily lives. While these may not always be by-products of publicity, police agencies should be aware of them as they plan their campaigns. A possible solution to reduce heightened anxiety is for police departments to reach out to community members, explaining the reasons behind the anti-crime campaign.

Might a publicity campaign displace crime to an unprotected area, raising community concerns? Unfortunately, there is little information about publicity’s impact on displacement. However, research has shown that displacement caused by crime prevention efforts is relatively rare and, if it occurs, is minimal at best.33Fear of displacement should not hinder attempts to mount publicity campaigns, however, as proper planning and implementation can reduce the probability of such an outcome. For example, by alternating publicity across different neighborhoods, a police department can increase a campaign’s deterrent value by creating uncertainty in the offending population. Offenders will not know where the real risks are, reducing the incentives for them to go elsewhere to offend.

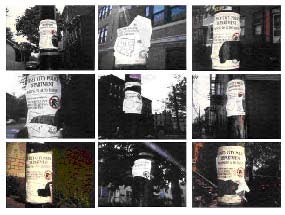

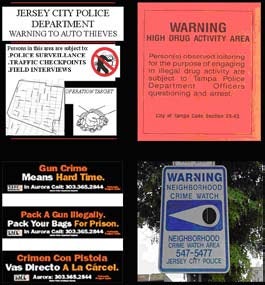

Vandals or concerned stakeholders who do not agree with the campaign may deface street signs or billboards. In this case, rapidly repairing or replacing damaged signs is important, as the message must not be diluted or otherwise lose its significance. Campaigns that rely on street signs or posters are particularly at risk of vandalism. Wherever possible, campaign planners should place signs out of reach. In New Jersey, a Jersey City campaign to prevent auto thefts suffered considerable amounts of vandalism, as seen below.

Poorly designed publicity campaigns are unlikely to produce the desired results. This section highlights some of the major considerations surrounding crime prevention publicity efforts.

To avoid problems, it is a good idea to pretest publicity campaigns with a sample target audience to ensure that the content has sufficient appeal and communicates the correct message.34

The campaign message comprises several important elements, discussed below.

The message content is any campaign’s central component.

When it is appropriate to identify the agency responsible for the publicity campaign, avoid giving off an air of superiority when delivering the message, as this may turn off the audience, leading them to reject it. There may be times, however, when not identifying the agency producing the publicity campaign may prove beneficial. For example, a campaign targeting graffiti problems is likely to fail if it is sponsored by the Department of Public Works. While this agency may be responsible for implementing and reaping the eventual benefits of the campaign, offenders may not respond very well to messages coming from such a nondescript, generic entity.

Trying to scare people is not recommended when deciding on a campaign’s content.

Publicity messages need to be relevant and offer specifics to the target audiences.

A well-designed logo can help to increase a publicity campaign’s impact. This notion comes directly from commercial advertisements that are highly laden with pictures, cartoon characters, and other appealing visuals to attract customer attention.

Police should base their decisions about geographic coverage on the aims of the campaign:

Campaigns that advertise crime prevention tips generally run longer than those that advertise a specific police operation, but they run the risk of leaving their target audience feeling bored and indifferent.48To avoid this problem, publicizing in “bursts” can be very effective. This method avoids drawn out, continual exposure to the message, but relies instead on short, focused, and intense bursts of information.49Research shows that repetition is an important factor when it comes to retention,50and small increments of publicity serve this goal well.

Campaigns that support police operations are often limited to the duration of the police intervention, but it is possible to begin the publicity before the intervention, and to continue it after the intervention ends. In this respect, publicity can amplify the perception of the police intervention, creating a greater deterrent effect. For example, if a police department develops a program to address auto thefts by implementing random checkpoints, the program can be advertised before, during, and after the operation. This informs offenders about the checkpoints but creates uncertainty as to when the police are actually out enforcing them.51

Implementation becomes especially relevant when the campaign is relatively short. Poor implementation protocols run the risk of reducing a campaign’s intensity and overall effectiveness. In mounting a campaign, police should ask the following:

It is important for police agencies to be aware of their target audience’s demographic composition. Publicity messages cannot be efficient if people cannot understand the basic content. Increased use of visuals and logos can promote messages more efficiently by relying on universally recognized symbols. This is important, for example, in populations with low literacy rates, or when addressing young children.

Having decided to implement a publicity campaign to advertise your crime prevention effort, should you adopt a general or a more tailored approach? The table below highlights some points to consider when choosing the publicity campaign’s format.

| General Format | Focused Format |

|---|---|

|

|

Too often, practical considerations such as ease of production and cost determine the format, even though it may not be the most effective one. While budgets are important, to select an effective publicity format, it is crucial to understand the target audience’s motivations and concerns. A common mistake is for police to think they know what message and format an audience will like and embrace. These decisions usually result in unattractive, poorly conceived, and ultimately ineffective campaigns.

A good example of a well-thought-out and appropriately chosen format is the “Spur of the Moment” comic book initiative Australia’s National Motor Vehicle Theft Reduction Council used to describe the risks young car thieves faced (see below).52In this case, the format spoke to the audience and increased the campaign’s success. Ideally, to maximize a campaign’s visibility, police agencies should rely on multiple avenues to disseminate information; relying on only one medium greatly reduces the campaign’s potential reach.53

“Spur of the Moment” comic book, Australia’s National Motor Vehicle Theft Reduction Council.

While national campaigns rely heavily on television or radio to address problems such as drug abuse and drunken driving, few police agencies rely on these media. However, television or radio spots can also be appropriate venues for local campaigns, as police departments can publicize efforts on the local news or in PSAs.54PSAs are often ineffective unless they target a very specific group, provide a very detailed message,55and air when the target audience is watching.56Unless donated, television time and the professional work needed to make attractive televised messages are expensive. Many cities have community access channels, but the audience tends to be limited, and it is unlikely that police campaigns that rely on these channels alone will have great impact.

National newspapers and magazines, like television and radio, are more suited for national campaigns. Local papers are more suitable for reaching a large segment of the local population, allowing them to read and learn about police interventions. Unlike television and radio, print media are relatively cheap, but it is difficult to control who receives the information. Simply printing a message does not ensure that the target audience will read it. In addition, because the information is mixed with other information, there is a chance the target audience may overlook it. With any printed media, you should always consider community or audience literacy levels.

Reno Gazette Journal 2004 Example of newspaper advertisement addressing mini-bikes. Reno Gazette Journal 2004

With their large imposing letters, billboards on highways and major roads ensure visibility. Billboards commonly advertise crime prevention techniques or otherwise educate the public about crime. In 2001, Los Angeles erected 60 billboards in gang-plagued neighborhoods carrying the message: “Guns ended the lives of 149 L.A. County kids last year. Stop the violence!” Billboards can also be useful in sharing target-hardening measures, as seen in the example below. While some billboard companies will donate space for public service messages, this medium is generally expensive. The design and production are also more elaborate than simple print media campaigns, and the message is confined to the billboards’ location.

Example of a billboard to educate motorists

Posters and signs are relatively inexpensive to produce, and they are easily posted in relevant areas. Police agencies can place signs in specific areas, increasing the chances they will reach key audiences. Posters can be moved from location to location following police activity, but they are vulnerable to vandalism and destruction. Some communities may also have ordinances against posting signs on utility poles. Finally, plastering posters in a neighborhood may raise concerns about aesthetics or questions about safety.

Posters and signs designed to warn offenders.

Ease of production and low distribution costs make fliers and leaflets favorites of police departments and other crime prevention agencies. Using readily available desktop publishing software, an agency can create a cost-effective publicity campaign. Police officers can deliver the material door-to-door or place it on car windshields.

Mailings are also an effective method of distribution, but materials should be addressed to an individual, instead of “occupant” or “resident,” as this personalizes the message.57While some studies have shown newsletters and brochures to be effective ways to spread crime prevention information,58such media do not always produce the intended result. In the early 1980’s, the Houston Police Department failed to reduce residents’ fear of crime by distributing newsletters containing local crime rates and prevention tips.59In Newark, N.J., the police department used a similar strategy; while people liked receiving the newsletters, they rarely read them.60

Key chains reminding owners to lock their cars can be distributed at local stores, pencils or colorful stickers with messages against violence can be given to schoolchildren, and cards reminding drivers about the fines for speeding can be printed on the back of tollbooth tickets. A good example of an alternative medium was used in Birmingham, England, where police started mailing out Christmas cards during the holiday season to residents living in crime hotspots, offering them crime prevention tips.61In a similar vein, Manchester, England, police sent holiday cards to known offenders in the area, reminding them to be on their best behavior by stating: “We are looking out for you.”62

Other means to spread a message include coasters, as seen in the London Metropolitan Police effort to reduce drug use.63This is an example of a cheap yet visible method to state your message or warning concerning the effects of drug abuse.

Coasters used to warn public about the dangers of drug use.

During one campaign for responsible alcohol consumption, a partnership was formed between bars, a National Football League (NFL) team, beer wholesalers, and police. An advertisement aimed at reducing victimization around bars was printed on table toppers, with the NFL coach giving “tips.” The beer wholesalers agreed to distribute the table toppers as they delivered their product. Thus, the drinking public in bars and restaurants was specifically targeted.

As mentioned above, comic books can be a useful way to reach youths. A phone company in England created an educational comic book for children to address the problem of phone vandalism.64On page 26 is an example of a comic book designed to reduce car theft.65

Without an evaluation, police departments will learn little about a campaign’s successes or pitfalls, and there will be little evidence to support future use of the campaign. A valid evaluation should focus on two components of the campaign: its actual implementation (process) and the result (impact).

The process evaluation will determine if the agency carried out the intended plan for the publicity campaign. For example, if the campaign plan included weekly radio ads and posters in business storefronts, the process evaluation would measure the extent to which police met these weekly targets.

A process evaluation for publicity campaigns should ask the following questions:

The above questions are important, as they will guide the impact evaluation and provide contextual information about the overall effort’s success or failure. If the process evaluation reveals that police poorly implemented the campaign, its effectiveness will remain questionable.

The impact evaluation will answer the basic question: Did the campaign have the desired effect? While the rate of the targeted crime problem is the first obvious measure, police departments should also consider other indicators when carrying out an impact evaluation of a publicity campaign. A community offended by a campaign’s content may easily offset the gains of a minor crime reduction. A thorough impact analysis should consider measuring how a campaign affects:

To carry out an effective campaign evaluation, police agencies must think ahead and gather the requisite data for meaningful comparisons and analyses. Departments should have valid and reliable indicators of the measures discussed above to allow for pre-and post-campaign comparisons.

A good way to test the effectiveness of crime prevention messages is to select an area similar to the one chosen for the campaign to serve as a control group, not exposing it to campaign information.66The control group will help in determining whether any changes observed are attributable to the campaign and not to other factors. An impact evaluation would then compare crime rates or resident behaviors between the two groups. In some cases, such comparisons can be misleading, however, as the publicity component may lead to a simple increase in crime reporting, falsely increasing the “crime problem.”67

Publicity campaigns have had mixed success when used in crime reduction programs. Perhaps publicity campaigns fail in delivering their intended message because of poor design or implementation, and hence, it may be premature to dismiss campaigns as ineffective crime prevention tools. While publicity attempts have had little success in changing victim or offender behavior, they should not be abandoned; rather, the police should refine them. The challenge lies in finding the proper ways to influence citizen behaviors. Finding ways to reach the public is a key component. For example, if we know that elderly women living alone have a greater fear of crime, police should seek greater campaign efficiency by addressing this group more directly.68Police in England reported that only 29 percent of residents had heard about an anti-burglary initiative they conducted.69In this case, it is clear that the publicity component did not reach the intended audience.

In order to achieve the intended goals, police publicity campaigns should do the following:

Click here for PDF of Appendix B: Summary of Previous Publicity Efforts

[1] Geva and Israel (1982).

[2] Brown and Wycoff (1987).

[3]Riley and Mayhew (1980)[Full Text]; Burrows and Heal (1980)[Full Text].

[4]Van Dijk and Steinmetz (1981).

[5] Riley and Mayhew (1980)[Full Text].

[6] Burrows and Heal (1980)[Full Text]; Riley and Mayhew (1980)[Full Text].

[7] Sacco and Trotman (1990).

[8] Riley and Mayhew (1980). [Full Text]

[9] Sacco and Silverman (1982).

[10] Johnson and Bowers (2003).

[11] Simmons and Farrell (1998).

[12] Wortley, Kane, and Gant (1998).

[13] Laycock (1991).

[14] Wortley, Kane, and Gant (1998).

[15] Cornish and Clarke (1986)[Full Text].

[16] www.popcenter.org/Problems/gun_violence/.

[17] Decker (1972); McNees et. al. (1976); Riley & Mayhew (1980)[Full Text]; Riley (1980)[Full Text].

[18] Sacco and Trotman (1990).

[19] Riley and Mayhew (1980). [Full Text]

[20] Laycock and Tilley (1995).

[21] Poyner (1988).

[22] Corbett (2000).

[23] Glendon and Cernecca (2003).

[24] Laycock (1991); Bowers and Johnson (2003)[Full Text].

[25] Simmons and Farrell (1998).

[26] Laycock (1991).

[27] Smith, Clarke, and Pease (2002)[Full Text]; Bowers and Johnson (2003)[Full Text].

[28] Barthe (2004). [Abstract only].

[29] Schaefer and Nichols (1983).

[30] Rice and Atkin (1989).

[31] Schneider and Kitchen (2002).

[32] Winkel (1987).

[33] Hesseling (1994).[Full Text]

[34] Wyllie (1997).

[35] Sacco and Silverman (1982).

[36] Derzon and Lipsey (2002).

[37] Gorelick (1989).

[38] Beck (1998).

[39] Borzekowski and Poussaint (1999).

[40] Atkin, Smith, and Bang (1994).

[41] Scottish Office Central Research Unit (1995).

[42] Schafer (1982).

[43] O’Malley (1992).

[44] Atkin, Smith, and Bang (1994).

[45] Holder and Treno (1997).

[46] Derzon and Lipsey (2002).

[47] O’Keefe (1986).

[48] Riley and Mayhew (1980). [Full Text]

[49] Riley and Mayhew (1980). [Full Text]

[50] Hallahan (2000).

[51] Johnson and Bowers (2003).

[52] www.aic.gov.au/conferences/cartheft/skelton.pdf.

[53] Kuttschreuter and Wiegman (1998).

[54] Holder and Treno (1997).

[55] Borzekowski and Poussaint (1999).

[56] Palmgreen et al. (1995).

[57] Lavrakas (1986).

[58] Beedle (1984).

[59] Brown and Wycoff (1987).

[60] Williams and Pate (1987).

[61] www.birmingham101.com/101news2002dec4.htm.

[62] www.manchesteronline.co.uk/news/s/25/25557_cops_ warn_yule_be_sorry.html.

[63] www.met.police.uk/drugs.

[64] Bridgeman (1997).

[65] www.streetwize.com.au/publications_legal.html.

[66] Derzon and Lipsey (2002).

[67] Sacco and Silverman (1982).

[68] Sacco and Silverman (1982).

[69] Mawby and Simmonds (2003).

Atkin, C., S. Smith, and H. Bang (1994). “How Young Viewers Respond to Televised Drinking and Driving Messages.” Alcohol, Drugs, and Driving 10(3/4):263–275.

Barthe, E. (2004). “Publicity and Car Crime Prevention.” In M. Maxfield and R. Clarke (eds.), Understanding and Preventing Car Theft, Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 17. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press. [Abstract only]

Beck, J. (1998). “100 Years of ‘Just Say No’ Versus ‘Just Say Know’: Reevaluating Drug Education Goals for the Coming Century.” Evaluation Review 22(1):15–45.

Beedle, S. (1984). Citizen Response to Burglary Information Brochures: A Follow-Up Study. Portland, Ore.: Portland Police Bureau, Public Affairs Unit, Crime Prevention Section. [Full Text]

Borzekowski, D., and A. Poussaint (1999). “Public Service Announcement Perceptions: A Quantitative Examination of Antiviolence Messages.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 17(3):181–188.

Bowers, K., and S. Johnson (2003). The Role of Publicity in Crime Prevention: Findings From the Reducing Burglary Initiative. Home Office Research Study No. 272. London: Home Office. [Full Text]

Bridgeman, C. (1997). “Preventing Pay Phone Damage.” In M. Felson and R. Clarke (eds.), Business and Crime Prevention. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press.

Brown, L., and M. Wycoff (1987). “Policing Houston: Reducing Fear and Improving Service.” Crime and Delinquency 33(1):71–89.

Burrows, J., and K. Heal (1980). “Police Car Security Campaigns.” In R. Clarke and P. Mayhew (eds.), Designing Out Crime. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.[Full Text]

Corbett, C. (2000). “A Typology of Drivers’ Responses to Speed Cameras: Implications for Speed Limit Enforcement and Road Safety.” Psychology, Crime, and Law 6(4):305–330.

Cornish, D., and R. Clarke (eds.) (1986). The Reasoning Criminal: Rational-Choice Perspectives on Offending. New York: Springer-Verlag. [Full Text]

Decker, J. F. (1972). “Curbside Deterrence: An analysis of the Effect of a Slug Rejection Device, Coin View Window and Warning Labels on Slug Usage in New York City Parking Meters.” Criminology 10(1):127-42.

Derzon, J., and M. Lipsey (2002). “A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Mass Communication for Changing Substance-Use Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior.” In W. Crano and M. Burgoon (eds.), Mass Media and Drug Prevention: Classic and Contemporary Theories and Research. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Geva, R., and I. Israel (1982). “Antiburglary Campaign in Jerusalem: Pilot Project Update.” Police Chief 49(4):44–46.

Glendon, A., and L. Cernecca (2003). “Young Drivers’ Responses to Anti-Speeding and Anti-Drink-Driving Messages.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behavior 6(3):197–216.

Gorelick, S. (1989). “‘Join Our War’: The Construction of Ideology in a Newspaper Crimefighting Campaign.” Crime and Delinquency 35(3):421–436.

Hallahan, K. (2000). “Enhancing Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity To Process Public Relations Messages.” Public Relations Review 26(4):463–480.

Hesseling, R. (1994). “Displacement: A Review of the Empirical Literature.” In R. Clarke (ed.), Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 3. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press.[Full Text]

Holder, H., and A. Treno. (1997). “Media Advocacy in Community Prevention: News as a Means to Advance Policy Change.” Addiction 92(6) (Supp. 2):S189–199.

Johnson, S., and K. Bowers (2003). “Opportunity Is in the Eye of the Beholder: The Role of Publicity in Crime Prevention.” Criminology and Public Policy 2(3):497–524.

Kuttschreuter, M., and O. Wiegman (1998). “Crime Prevention and the Attitude Toward the Criminal Justice System: The Effects of a Multimedia Campaign.” Journal of Criminal Justice 26(6):441–452.

Lavrakas, P. (1986). “Evaluating Police-Community Anticrime Newsletters: The Evanston, Houston, and Newark Field Studies.” In D. Rosenbaum (ed.), Community Crime Prevention: Does It Work? Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

Laycock, G. (1991). “Operation Identification, or the Power of Publicity?” Security Journal 2(2):67–72.

Laycock, G., N. Tilley (1995). “Implementing Crime Prevention.” In M. Tonry and D. P. Farrington (eds.)Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime PreventionChicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mawby, R., and L. Simmonds (2003). “Homesafing Keyham: An Evaluation.” Community Safety Journal 2(3):20–30.

McNees, M., D. Egli, R. Marshall, J. Schnelle, and R. Todd (1976). “Shoplifting Prevention: Providing Information Through Signs.” Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 9(4):399–405.

Monaghan, L. (1988). “Anatomy of a Crime Prevention Publicity Campaign.” In D. Challinger (ed.), Preventing Property Crime. Seminar Proceedings, No. 23. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology.

O’Keefe, G. (1986). “The ‘McGruff’ National Media Campaign: Its Public Impact and Future Implications.” In D. Rosenbaum (ed.), Community Crime Prevention: Does It Work? Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

O’Malley, P. (1992). “Burglary, Private Policing, and Victim Responsibility.” In P. Moir and H. Eijkman (eds.), Policing Australia: Old Issues, New Perspectives. South Melbourne, Australia: Macmillan.

Palmgreen,P., E. Lorch, L. Donohew, N. Harrington, M. Dsilva, and D. Helm (1995). “Reaching At-Risk Populations in a Mass-Media Drug Abuse- Prevention Campaign: Sensation-Seeking as a Targeting Variable.” Drugs & Society 8(3/4):29–45.

Poyner, B. (1988). “Video Cameras and Bus Vandalism.” Journal of Security Administration 11(2):44–51.

Rice, R., and C. Atkin (eds.) (1989). Public Communication Campaigns. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Riley, D. (1980). “An Evaluation of the Campaign To Reduce Car Thefts.” In R. Clarke and P. Mayhew (eds.), Designing Out Crime. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.[Full Text]

Riley, D., and P. Mayhew (1980). Crime Prevention Publicity: An Assessment. Home Office Research Study No. 63. London: Home Office. [Full Text]

Sacco, V., and R. Silverman (1982). “Crime Prevention Through Mass Media: Prospects and Problems.” Journal of Criminal Justice 10(4):257–269.

——— (1981). “Selling Crime Prevention: The Evaluation of a Mass Media Campaign.” Canadian Journal of Criminology 23(2):191–202.

Sacco, V., and M. Trotman (1990). “Public Information Programming and Family Violence: Lessons From the Mass Media Crime Prevention Experience.” Canadian Journal of Criminology 32(1):91–105.

Schaefer, R., and W. Nichols (1983). “Community Response to Crime in a Sun-Belt City.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 10(1):35–46.

Schafer, H. (1982). “Frauen bei Nacht—Women by Night: Analysis of a Warning-Leaflet Campaign.” In E. Kuhlhorn and B. Svensson (eds.), Crime Prevention, Report No. 9. Stockholm, Sweden: National Council for Crime Prevention.

Schneider, R., and T. Kitchen (2002). Planning for Crime Prevention: A Transatlantic Perspective. London; New York: Routledge.

Scottish Office Central Research Unit (1995). Evaluation of the Scottish Office Domestic Violence Media Campaign. Edinburgh, Scotland: Author.

Simmons, T., and G. Farrell (1998). Evaluation of North Brunswick Township Police Department’s Community-Oriented Policing Project To Prevent Auto Crime. North Brunswick, N.J.: North Brunswick Township Police Department.

Smith, M., R.V. Clarke., K. Pease (2002). “Anticipatory Benefits in Crime Prevention” In N. Tilley (ed.), Analysis for Crime Prevention, Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 13. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.[Full Text]

Van Dijk, J., and C. Steinmetz (1981) Crime Prevention: An Evaluation of the National Publicity Campaign. The Hague, Netherlands: Netherlands Ministry of Justice.

Williams,H., and A. Pate (1987). “Returning to First Principles: Reducing Fear of Crime in Newark.” Crime and Delinquency 33(1):53–70.

Winkel, F. (1987). “Response Generalisation in Crime Prevention Campaigns: An Experiment.” British Journal of Criminology 27(2):155–178.

Wortley, R., R. Kane, and F. Gant (1998). “Public Awareness and Auto-Theft Prevention: Getting It Right for the Wrong Reason.” Security Journal 10(2):59–64.

Wyllie, A. (1997). “Evaluation of a New Zealand Campaign Towards Reduction of Intoxication on Licensed Premises.” Health Promotion International 12(3):197–207.

Important!

The quality and focus of these submissions vary considerably. With the exception of those submissions selected as winners or finalists, these documents are unedited and are reproduced in the condition in which they were submitted. They may nevertheless contain useful information or may report innovative projects.

Invercargill - The RAID Squad Initiative, New Zealand Police Department (NZ), 1998

KIDestrian: Child Pedestrian Safety [Goldstein Award Finalist], Hamilton-Wentworth Regional Police (ON, CA), 1994

Operation Cease Fire [Goldstein Award Winner], Boston Police Department, 1998

Operation Pasture [Goldstein Award Winner], Lancashire Constabulary, 2008

Preventing Theft from Auto [Goldstein Award Finalist], Edmonton Police Service, 1994

Safer Travel at Night Campaign [Goldstein Award Winner], Transport for London (London, UK), 2006

Team: Reducing Vehicle Burglaries [Goldstein Award Finalist], Carrollton Police Department, 2005

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.